Dykes on Land: How Lesbians Created Community Outside of Patriarchal Society

During my time as a summer intern at the Lesbian Herstory Archives, I had the amazing opportunity of rehousing and processing numerous collections on-site. One that really piqued my interest and led me to research more at the archives was a collection on Northwoods Women’s Land in Alpine, NY. This collection was my first larger collection that I processed, and it was on something I hadn’t had the opportunity to learn about yet: lesbian lands! Within this collection was a draft of Joyce Cheney’s “Lesbian Land”, numerous message books written between the collective, flyers, and correspondence regarding events and visitors at Northwoods, and some information on gardening and farming. After learning about other women’s lands through the information in this collection, I decided to review our organizational files to see if we had any information on the ones mentioned, and we did. I found organizational files on the Pagoda Temple of Love, Sugarloaf Women’s Village, and Arf Women’s Land, as well as a collection on A Woman’s Place in the Adirondack Mountains.

The lesbian land movement began in the 1960s and 1970s during the “Back to the Land Movement”. This movement became increasingly popular due to many Americans realizing they didn’t have familiarity with the land they lived on or how to sustain themselves with basic needs such as food and shelter. Additionally, the political events of the time, including the Watergate Scandal, the 1973 oil shock, and the Vietnam War, demonstrated government failings to the American people, leading many folks to become self-reliant and move from urban to rural areas to establish communes across the country. Many of these communes consisted of lesbian lands, created by lesbian feminists and separatists who made the conscious decision to separate themselves from patriarchal society. These lands were a way for lesbians to refigure their identities, create safe community spaces for themselves, and detach themselves from a male-centered and dominated society.

The original collective of Northwoods Women’s Land consisted of five women named Earth, Hawk, Dust, Jesse, and Shad, and was created in 1977. There’s more information on the formation of this collective in a letter left by the donor of this collection. Looking at the message books inside, these books were placed in a communal space on the land where the collective spent a good amount of time. These message books were a way for the collective to write to one another when folks were busy working on the land. The entries included good morning and goodnight messages, upkeep reminders, notice of future guests, farming notes, and general discourse. The messages are either addressed to one person specifically or to the collective as a whole. Although Northwoods had numerous community events of their own and ones inviting the outside world, these message books are a testament to the connection between the collective of Northwoods. It also serves as a reminder that communication is the key to sustaining a supportive and lasting community.

Acro Iris (Rainbow) is a non-profit survival camp for Native womyn of color and their children located in Ponca, Arkansas. I found information on this land within the collection I processed on Northwoods. Perspectives on living on the land from Native Americans are crucial to the conversation when it comes to learning about how to care for the land that is considered part of the United States. Native Americans lived and cultivated life on this land before colonization, and knowing their history and the ways they cared for the indigenous plants and animals is imperative to the conversation on environmental practices in the U.S. According to a letter typed by the folks at Acro Iris in the Northwoods collection, “Acro Iris is a shelter for womyn and children who are recovering from or escaping various troubled and abusive living situations…or who just need a rest from the stress of the pollution of the city.” This camp/shelter was run by two Native queer womyn, Sunhawk and Miguela, and was founded in 1987. A part of their purpose is to “learn and then teach the old ways of the original people of this continent, Turtle Island, to the young people who come here.” The womyn of Acros Iris garden and raise animals using organic and natural methods, teach plant identification, and encourage natural healing. Something that sets Acro Iris apart from the other lands that I mention in this post, other than the fact that this collective is native to the land they inhabit, is that more children were staying there than womyn! Their focus is on protecting and informing the next generation and seeing that the old ways of living on the land will not be lost to the children. Through the information we have on Acro Iris, I also learned that Acro Iris made reusable 100% cotton menstrual pads. They made these to promote ecological concerns on recycling, to combat the risk of toxic shock, and to make menstrual care more affordable by providing a pad that can last up to two years. A pamphlet to order these pads was found in the Northwoods collection and provides size suggestions and washing directions. The last couple of materials I found were on Rainbow Medicine, which is a cottage industry of Acro Iris that specializes in herbal remedies and blends. Within the papers, you can find information on ingredients and steps for herbal formulas on treatments for arthritis, blood pressure, colds, and more. Information on the current work and programs of Acro Iris can be found on their website, https://www.arcoirisearthcareproject.com/.

A lesbian land that I not only found in Joyce Cheney’s “Lesbian Land”, but also the organizational files at LHA, is Arf Women’s Land, organized under a folder titled “New Mexico’s Women’s Land Trust”. Arf started as a lesbian-feminist movement in the 1970s and still exists today. According to the land’s website, “since 1977 ARF has been a sanctuary for hundreds of lesbians, women, and children from all over the world” (ARF Women’s Land, n.d.). New Mexico Women’s Land Trust is a non-profit membership organization founded so that Arf and other women’s lands alike can be owned collectively by the women’s community. Arf Women’s Land is a way for women to live together on land, free from male-dominated spaces, and to connect with the earth in ways they wouldn’t be able to in mainstream society. The women of Arf have ecological practices that allow them to learn from nature the kind of society they want to build. According to “Lesbian Land”, this land is very open, with no rules. “The Arf women explained that there is always tension in life. Enforcing rules make tension and resentment” (Cheney 1985). The activities of the women at Arf included “punk rock and rugby, meditate, hike, heal, go to alcohol recovery programs, have healing festivals, and no nuke circuses and demonstrations, bicycle, mother,” and more (Cheney 1985). I can only imagine the joy these moments brought to the women of Arf. Looking around and seeing a collective of folks having the opportunity to safely engage in community bonding and building.

Another lesbian space I found in Cheney’s “Lesbian Land” as well as the organizational files at LHA was The Pagoda Temple of Love. The Pagoda was a community of lesbians who owned land together in Vilano Beach near St. Augustine, Florida. It came into existence on July 7th, 1977, when two lesbian couples who did women’s theater decided to buy a house together. In the quest for looking for a home, the women struck a deal for four cottages at $1,000 less than the initial price. So they took it and started a theater collective that would eventually become a resort for women to go to for lively community events or to seek a healing space. Through the organizational file, I learned that Pagoda was a healing community space designed to provide opportunities for lesbians. Some examples of the opportunities listed are: classes in exercise, dance, psychic awareness, group and individual therapy, sports and physical therapy, concerts, performances, and workshops, with facilities such as a library, game room, and lounge. They also wanted to provide natural healthcare and alternatives to drugs to challenge cultural attitudes on death and aging. Lesbians of all generations have made it a priority to provide resources for their community, even in times of political uncertainty.

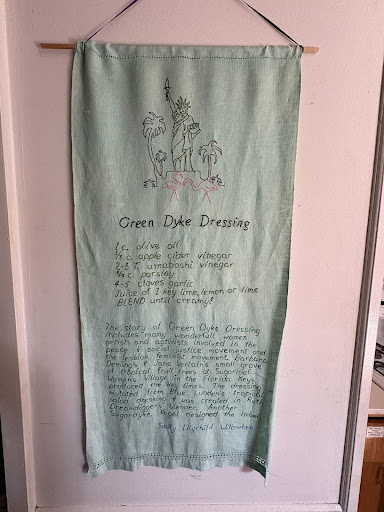

Lastly, a lesbian land I would like to touch on is Sugarloaf Women’s Village in the Florida Keys. Not only does LHA have an organizational file on this village, but hanging in the kitchen of the archives is an embroidered tapestry with the ingredients of Green Dyke Dressing made by Sally Lilychild Willowbee. This recipe contains a single key lime, which comes from Sugarloaf’s small grove of tropical fruit trees. With some information from the organizational files, I learned that a key purpose of Sugarloaf is to create a safe community where the physical, emotional, cultural, and spiritual well-being of lesbians of varying race, class, age, and ability is promoted. Additionally, Sugarloaf recognizes the need to provide space and opportunity for lesbians to live in community and do this to counter the intensely individualistic nature of the dominant society. Aside from the resources we have on site, I learned a bit about Sugarloaf from Jennifer Meyer’s blog post from her trip to the village in 2016, titled “Sugarloaf Women’s Village” (Meyer 2016). Meyer recognizes that the land was originally bought by Barbara Deming in the mid-70s during the Back to the Land Movement. When she passed away, Barbara left the land to her lifelong partner, Jane Verlaine, who left it to a villager named Blue Lunden. Blue passed away in 1999, but before she did, she created the Sugarloaf Women’s Land Trust. This land trust leaves the property dedicated to all lesbians, meaning lesbians from all over are free to visit, and those who wish to stay long can apply for residency. The thought of putting the land into a land trust dedicated to lesbians is a beautiful sentiment. Making sure future generations of lesbians have a space to enjoy community and be with one another outside of capitalist society is extremely important to the well-being and building of our community. Especially considering we’re in the digital age, where many young folks are hesitant or lost when it comes to being active in queer communities and spaces. This space provides the opportunity for lesbians all over to connect with one another face to face, instead of through a comment section.

It is important to become educated on the efforts of lesbians before us and their history. And it’s incredible to know that previous generations of lesbians were looking out for the future generations. Community is always there; what’s important is maintaining those connections and stepping outside of your comfort zone to nourish it. Lesbian lands provided powerful healing spaces and community building for lesbians throughout the end of the 20th century. Some of those collectives are still alive today, pay them a visit if you can!

Works Cited

- Acro Iris. “Acro Iris: Earth Care Project.” Accessed July 22, 2025. https://www.arcoirisearthcareproject.com/

- Arf Women’s Land. “Arf Community Women’s Land: New Mexico.” Accessed July 21, 2025. https://www.arfwomensland.com/

- Meyer, Jennifer. “Sugarloaf Women’s Village,” One Year on the Road, February 17, 2016, https://www.oneyearontheroad.com/sugarloaf-womens-village/

- Cheney, Joyce. Lesbian Land. Word Weavers, 1985.

Thanks for your work and for the excellent write-up. I’m sure there’s more but you might want to look at Rose Norman’s recent book on “The Pagoda: a Lesbian Community By the Sea,” SinisterWisdom , 2023. And yes, it was better times! Keep up your research.

This is a lovely historical piece. The author really has it together and did a great job of documenting and sharing.

Glad to know of these in addition to continuing to celebrate the Combahee River Collective.