A Queer Guide to Personal Digital Archiving

Intro

Let’s just dive right in by defining what an archive is. You may be more familiar with a physical archive, or at least the popular vision of one: dusty books and manuscripts piled high to the ceiling, full of knowledge and cursive handwriting. That is the case for some archives, sure, but we can describe an archive as a collection of “permanently valuable records—such as letters, reports, accounts, minute books, draft and final manuscripts, and photographs—of people, businesses, and government” which are preserved to be accessed at later dates (SAA). Archives aim to maintain original published and unpublished documents with specific parameters for how they are accessed by patrons, while libraries disseminate published materials and can replace copies if they are lost or damaged. For digital records, databases are neither libraries or archives, but rather a tool used by both to store and organize information for easy retrieval. In a very basic sense, an archive is a collection of stuff that someone or a lot of someones want to preserve for the future. With that definition out of the way, we can start to get more specific:

- Public archives are collections of government (federal and local) and public institutions’ materials. For example: NYC Department of Records, the National Archives, and the American Archive of Public Broadcasting.

- Community archives constitute smaller, grassroots operations and collections that serve specific communities (often marginalized or misrepresented), like the Lesbian Herstory Archives, Archivo Histórico Casa Pueblo, and People Archive of State Violence.

- A private archive collects materials from non-public organizations or individuals and is only accessible to a select group of people. Examples include charitable organizations, some museum collections, corporate bodies, and churches.

- Personal archives are a subsection of private archives, traditionally individual or family collections made up of personal papers, records, and ephemera. These collections are often left to institutions like museums, archives, and universities for safekeeping and historical research.

It should be noted that many archives have a hybrid of public and private materials. Some, like LHA, have materials that the public can access only by appointment. University archives are often private in the sense that they are only accessible to their students, faculty, and affiliates, with potential public access by request. When it comes to accessibility (beyond physical access accommodations), all archives must consider copyright restrictions. Libraries carry published materials and have licenses to allow patrons to check out these publications for limited periods of time, but archives often carry unpublished and restricted materials. Unpublished materials donated by the creator can be accessed and shared if the creator has given rights to the archive or they can deny access and limit the visibility of their work. For example, I reprocessed a special collection where the donor gave full permissions to the archive to share her manuscripts but also donated a box of materials not to be opened until after both her and her partner’s deaths. Sometimes, items enter an archive without any notation on permissions, so it often defaults to being restricted. If you do decide to donate your work or collections to an archive in the future, be sure to note desired restrictions and ownership.

Today, many archives are a hybrid of physical and digital materials and resources. This can be as simple as a virtual document describing what is contained in the archive all the way to digital materials accessible to anyone with an internet connection. Digital archives can be a hybrid of digitized and born-digital materials or solely focused on one of the two. Digitized materials are items that are originally physical, like a book or DVD, but have been scanned or photographed so as to be available digitally. Born-digital materials do not have a physical form to begin with, such as photographs taken on a smartphone, emails, and webpages.

Start Your Collection

Maybe you don’t have materials for an archive yet and are just reading this blog post out of sheer curiosity – I encourage you to start! You may know the phrase, “history is written by the winners”, but I would like us to rewrite it to “history is written by those who are organized”. It’s not very catchy and I know how hard it can be to stay organized (I am currently operating on 30+ open tabs and no file naming conventions for my documents), but with the right action plan, you too can be an archivist and record your history! We are living in an era in America where words like “queer”, “transgender”, and “diversity” have been banned for federal agencies and bills limit or ban gender-affirming healthcare. It is on us to record, preserve, and share our histories – to set the record straight that we live and thrive despite the limitations and violence imposed by those in power. By having a hand in our own histories, we also have the power to omit: you do not have to save everything or anything. It is entirely your choice to archive and share your life with others – “there’s nothing inherently radical about a preservationist politics, nothing inherently life-saving about saving files” (Adair). Whatever you put online or send to an archive (or even what you keep on Google Drive) will be seen by people you don’t know. Your safety should come first, but consider when you were early in realizing your queerness – what did you read, watch, or hear that allowed you to find the right words to describe yourself and find spaces to connect with queer community? If you want to be a part of archived queer history, here are some places to start:

Keep a diary: There are plenty of benefits to journaling, and it gives you the chance to document your unique experiences and feelings with timestamps for events. I personally struggle to keep up the practice, but I ramble in the notes app on my phone every now and then. Looking back on them reminds me where I was mentally a few years ago, for better or worse. Early personal and private archives contained diaries that have informed many biographies and histories (for example, Anne Frank, Harry Truman, Lady Murasaki, and Charles Darwin)

Take a LOT of photos: at the club, in your home, on a hike, of your lover, with your friends – photography has never been more accessible. You can start with your smartphone or a disposable camera and a film scanning service (search for local options such as B&H, Brooklyn Darkroom, or CVS).

Take videos: Bad for storage space, great for vibes: the iconic longer format image. From videos of your wife blowing out her birthday candles or a full-length indie film, the sky’s the limit! (or, more realistically, your storage space is the limit)

Keep a pen pal via handwritten letters or email: Many private and special collections contain correspondence. You can also support incarcerated queer folks with the Prisoner Correspondence Project or Prison Library Support Network!

Write stories: Fiction is an exciting place to explore queer themes and relationships, especially if you involve yourself in fandom spaces. You can get started writing and posting fanfiction on Archive Of Our Own, posting short stories and poems on a blog, or using apps like Scrivener to get a novel rolling!

Record oral histories: from yourself, friends, family, people you just met, and more. Oral tradition is the oldest and most widespread form of preserving and sharing history and cultural knowledge. A member of LHA built an incredible website of lesbian oral histories!

Make art: painting, directing, dancing, sculpting, singing – art can be a place of catharsis for yourself and a unique bridge between queer and non-queer viewers. Think about how long “Rent” was on Broadway (12 years), these stories are important to share!

Make note of the queer books, newspaper articles, zines, comics, and artworks you have collected yourself: These can also be donated to queer archives when you’re ready to let them go. I love to read and collect queer comics, so I’ve started logging them along with my books in LibraryThing. I also cross-reference my collection with the Grand Comics Database, a global, volunteer-run, open database of millions of comics, to help fill in missing information or add a new work.

Once you have a decent amount of material, you will need to start organizing and possibly digitizing.

Digitizing and Downloading

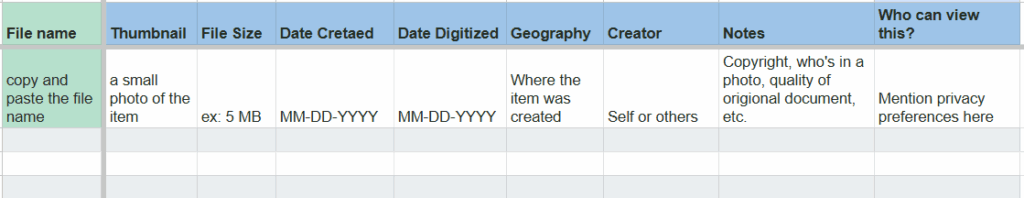

If you have a collection of physical documents that you would like to have accessible digitally, digitization is your first step. Digitizing is the process of converting physical materials into digital items. For photographs and paper documents, this often involves scanning or digitally photographing. The process of digitizing becomes trickier with older formats of audio and video tapes, often involving specific and expensive equipment. If you have older audio and or video formats such as VHS, floppy disks, vinyl, or cassettes, you may need to outsource (you can try reaching out to local or volunteer-run groups first, such as XFR Collective). Before you begin digitizing, make a plan for your file names and prepare space on your personal device for where these files will be downloaded. Your file names should be consistent and descriptive; for example, if you were saving a series of photographs from a trip to Italy, you could name files italy_june2025_01.png, italy_june2025_02.png, and so on. If you are digitizing items that were not created by you, keep note of that for each item, such as on a spreadsheet, for future reference. A spreadsheet is also helpful for descriptive metadata of your collections. Descriptive metadata provides context for items in your collection such as title, creation date, media type, author, and more. If you will be donating your collection(s) in the future, the more information you provide about the original item, the better. Here is an example template for what you could use for your collection.

You can also use the spreadsheet, or another document, to keep minutes and track your progress if you involve yourself with a larger archival project. This helps avoid redundant work later and understand where you are in the process so you or an archivist can pick up where you left off. You can arrange your materials in any way that makes sense to you, but make sure that you make a key, guide, or note about your reasonings for the arrangement and naming conventions. Think about if someone else were to receive your materials, how would they know how to navigate or begin interpreting the collection?

For digitizing flat objects (such as documents and photographs):

- Google PhotoScan is a free app for Android and IOS that takes multiple photos of a document or photographs to stitch the best quality photo. You can also back up the images in Google Photos.

- Microsoft Lens is another free app for Android and IOS that is built for documents but also can be used for photographs. If you are a OneDrive user, you have the option to backup images to the cloud.

- CamScanner is available on multiple platforms for scanning documents with options to email, fax, and print. I used this in 2020 during virtual college courses to scan class assignments and submit them as pdfs (I really like the option to scan text). I still use the app to this day to take scans of important documents such as my passport.

- If you have access to a flatbed scanner at work, school, or home, you can scan photos, documents, and books to send high-quality scans to your personal devices.

To digitize DVDs and CDs, you will need a built-in or external player to plug into your computer. If you are attempting to digitize Blu-ray or 4K discs, you may need more specific, expensive external players. Once you have the hardware for reading the discs, you will need software to save and convert your discs into digital files:

- For CDs, you can use free audio converters such as EZ or fre:ac

- When outputting/saving your CD files, the FLAC format will preserve the CD’s original quality, or you can save them as either MP3 or AAC for lower quality but smaller file sizes.

- For DVDs, you can use free converters such as Handbrake or use the free trial period for Winx DVD.

- The MKV file format will be the best for preserving HD DVD video, but will be the largest save file compared to other formats due to it preserving the original quality of the DVD. MOV is the best output file format for MacOS or Apple iOS while MP4 is the most compatible overall.

For bulk downloading born-digital materials:

- If you have a Gmail, here is how you can download your email data.

- Here is a tutorial for Outlook users.

- ePADD is a software that aids in archiving emails. The user guide is linked on the home page.

Social media data (most of these downloads are intending for backing up your data, but there are various methods to extract media from the downloaded file):

- Instagram and Facebook: go to accountscenter.facebook.com and log in. Go to Your information and permissions > Export your information and follow along the pop-up windows. You can select either HTML or JSON formats. This process can take up to two weeks depending on the amount of data you select to download.

- Twitter/X: Go to Settings and Privacy > Your account > Download an archive of your data > Request archive. This will produce a ZIP file that can be extracted on your PC.

- Tumblr: Click “Settings”, select the blog you’d like to export in the right sidebar, scroll down to “Export” then click the “Export [blog name]” button. Once your data is ready you will see a button to download a ZIP file from the same area.

- YouTube: From your profile dropdown menu, go to “Your data in YouTube”, press “more” under “Your YouTube Dashboard”, and press “Download data”. You can select what data you would like to download and either a ZIP or TGZ file format with multiple options for where the files will be sent.

- TikTok: From your profile, go to Settings and privacy > Account > Download your data, select what you would like to download and either a TXT or JSON file format, then hit Request data.

- The JSON file type would allow you to move your data to another platform or you can use a script like this one from amovitz on GitHub to create individual MP4 files (note that directories are also known as folders on your PC)

Storage Considerations

After digitizing your analog materials, consider if you would like to keep the physical items and where (you can note this in a spreadsheet). A popular practice in digital archiving is called LOCKSS: Lots Of Copies Keep Stuff Safe. The idea is, the more copies you have of an item, the safer it is from data loss. This could look like having a copy of a file on your personal device and on a cloud service. However, the more digital materials you save, the more it will cost to store. Here is a quick summary of a variety of file sizes and types:

| Memory Unit | Description |

| Kilo Byte (KB) | 1 KB = 1024 bytes |

| Mega Byte (MB) | 1 MB = 1024 KB |

| Giga Byte (GB) | 1 GB = 1024 MB |

| Tera Byte (TB) | 1 TB = 1024 GB |

| File Type | Average File Size* | Description |

|---|---|---|

| JPEG | 50 – 500 KB | Image file supporting lossy compression (sacrifices data and quality during compression for a smaller file) |

| PNG | 500 KB – 5 MB | Image file supporting lossless compression (maintains the original data of the image) |

| RAW | 20 – 70 MB | A file containing unprocessed data from a camera |

| TIFF | 100 MB – 2 GB | A file that supports both lossy and lossless compression while also storing raster graphics, header tags (metadata), and subfiles. |

| WAV | 10 MB – 1 GB | An uncompressed audio file |

| MP3 | 1 – 100 MB | An audio file supporting lossy compression |

| MP4 | 1 – 100 MB | An audio and video file |

| DOCX | 10 KB – 50 MB | A Microsoft Word file format for text and images |

| 100 KB – 50 MB | An Adobe file format for text and images |

*the file size ranges here are rough averages; file size can vary greatly depending on the camera, capture settings, video quality, length of content, and compression parameters

Be considerate of file size while you are digitizing and preparing digital files – the number of files and their size will determine the options and cost for personal storage, be it via cloud service or hardware. A cloud storage service, such as Google Drive, stores your data remotely on the provider’s servers so that you can access it from anywhere with an internet connection. Here are a few cloud storage options:

| Cloud service | Cost | Considerations |

| Google Drive (15 GB) | Free | Google Drive offers streamlined sharing for Google account users, especially if you are a student. |

| Google Drive (100 GB) | $1.99 / month | Your storage plan can be shared with 5 others. There is also a 2 TB storage plan for $9.99 / month |

| Microsoft 365 (5 GB) | Free | The free plan comes with every Microsoft account. Includes 15 GB of Outlook.com email storage. |

| Microsoft 365 Basic (100 GB) | $19.99 / year | This includes both 100 GB cloud storage and 100 GB mailbox storage. Only accessible by one person. There are 1 – 10 TB options and a family plan at higher subscription costs. |

| Dropbox (5 TB) | $18 / month | This standard plan allows for 3+ users and can transfer files up to 100 GB |

| IDrive (10 TB) | $20 / month | Backup for Google Workspace data with an extra $5 / month for each additional TB |

Google Drive is an affordable and accessible option for many, but there are some concerns that Google is training its AI assistant, Gemini, on user documents. Google’s help center purports that user content and data are not stored for training and, when prompting Gemini, only “use your prompt, relevant Workspace content, and webpage context to generate a response”, but it is up to you to decide how much you trust these claims. All cloud storage comes with the risk of data loss or privacy breaches, so it is more reliable from a security standpoint to store your documents on a personal hard drive. When purchasing a hard drive, you must consider your budget, space, and hardware requirements (some Mac laptops only have USB-C ports). Hard drives begin to get exceedingly expensive the more data you need to store, so you may need to consider downsizing your collection or relying on cloud services if options are unaffordable. Here is a list of options for hard drives:

| Hard Drive | Cost | Considerations |

| SanDisk Flash Drive (64GB) | $8.85 | 16GB to 256GB options, lightweight and small |

| SanDisk Cruzer Glide (256GB) | $20.14 | This is a USB-A model, but SanDisk offers many size and port options. |

| Kingston DataTraveler Max | $32.95 – $101.49 | 256GB to 1TB, USB-A and C options |

| Buffalo SSD-PUT (2TB) | $119.99 | Fair price per TB for portable options |

| Western Digital My Book Desktop External Hard Drive | $132.82 – $619.99 | 4TB – 26TB, not portable, for large collections |

It should be noted that hard drives are only a temporary storage space for your materials. Formatting can become obsolete and hardware can malfunction or break. When it comes to archival preservation, there is no perfect or final solution: the field and technology are constantly evolving – archives and collections must be revisited and reprocessed again and again. Once you have your collection saved to a cloud service or hard drive, be sure to check in regularly and plan for migration later when technology updates.

Design your Own Archive!

So you’ve got your folders and files and maybe even some spreadsheets – now what? If you’re just looking to preserve and organize your materials with the possibility of donating later, keep an eye on your cloud account or hard drives. This is also where you can practice intellectual arrangement, the organization of your documents into folders and subfolders to separate materials in ways that make sense to you (such as by theme, projects, time period, material, etc.). If you want to share your documents, there are some fun and creative ways you can make them accessible to others.

Make a roadmap of your collection(s) (optional but helpful): Create a document, such as a spreadsheet as mentioned in the digitization section, that includes your file naming conventions and current storage size of your files, then walk your potential viewer through your archive. Make notes about who’s in a series of photographs and where they were taken, leave a collection of resources that influenced a work of art, or include notes from your diary to link your internal and external experiences. This is also a helpful place to note if you would prefer some parts of your collection to remain private.

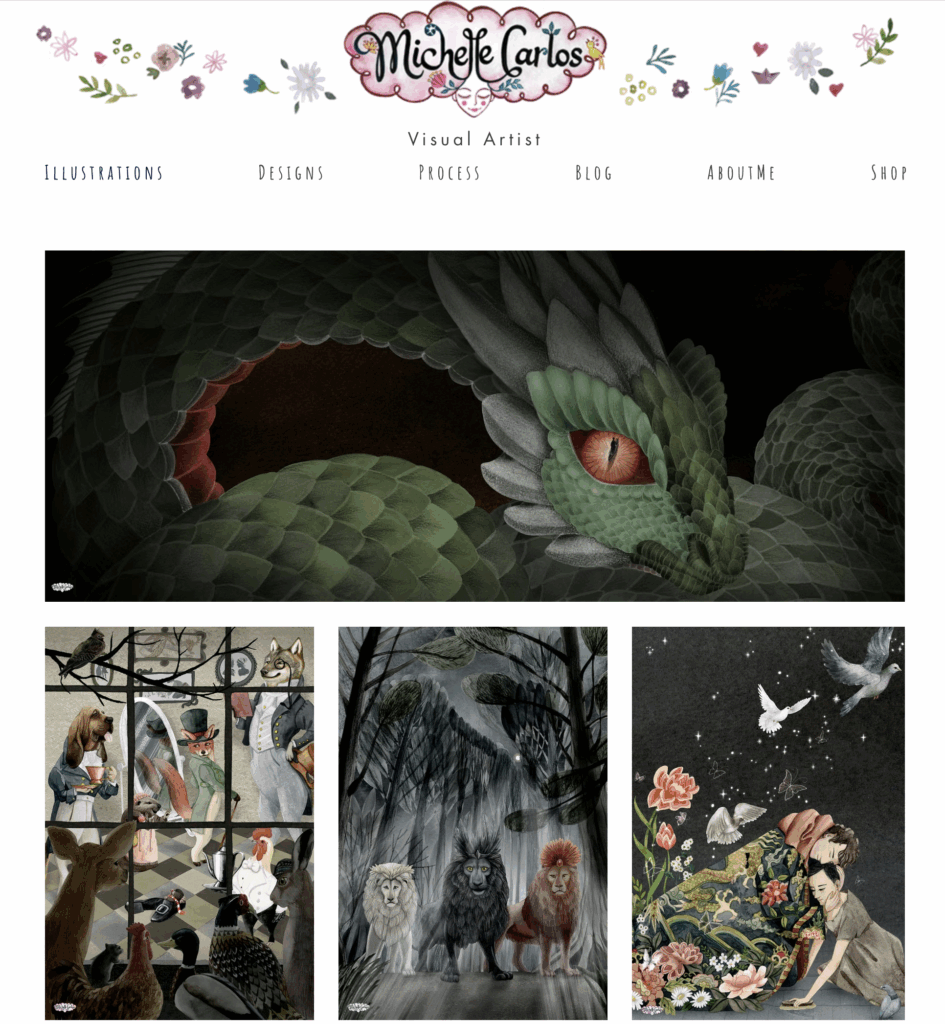

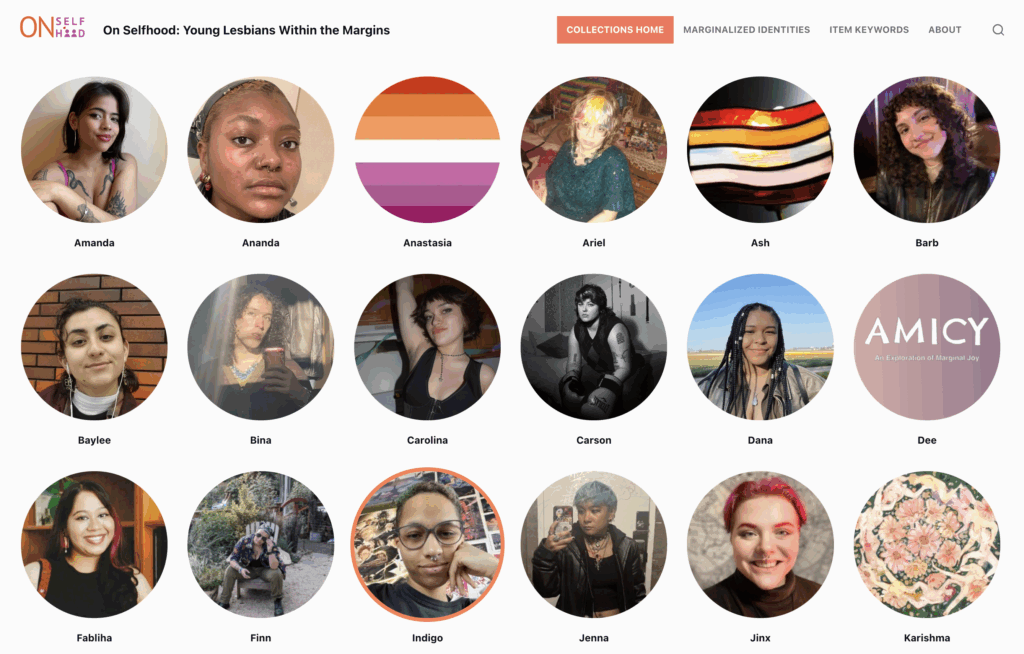

Create a website: This involves some level of tech-saviness, but there are a variety of options for all experience levels with software design. WordPress is one of the most popular site-building tools, along with Squarespace and Canva (links lead to tutorials for each). If you’re comfortable with coding, HTML and CSS will get you started with a bare-bones website, with plenty of fun add-ons with the addition of JavaScript and/or Python. This can look and act very similar to a portfolio.

From https://www.michellecarlos.com/

From https://www.multiplemarginalities.net/

Neocities: If you remember Geocities, making a Neocities website is a fun and interactive way to create an online and publicly accessible archive, especially if you make interactive content such as video games or have an online store. It is just a website, but it has a shared style and social history that can be exciting to join.

From https://petrapixel.neocities.org/

From https://twelvemen.neocities.org/

Design a database: For the more tech-savvy, you can design and build your own database with database management software, such as MySQL. If you’re not familiar with SQL, a querying language, you can head to W3schools to learn how to code and implement your database. This can take a lot of time if you’re new to coding and database design, so I would not recommend it unless you are already somewhat familiar with querying languages.

Donations

Even after you’ve created your archive, you still have the choice to delete it all. No one is forcing you to share your life – every privacy consideration is yours to make. As much as the purpose of this guide is to encourage queer people to preserve their ephemera in the face of institutional and political violence and erasure, it is also meant to give you a sense of autonomy over your life. You may feel empowered to preserve and share aspects of your life just as you may feel equally empowered to fade into obscurity. I would also like to acknowledge the anti-archival mindset: that being un-archived and untraceable is safe, anti-colonial, and queer. Archives are also not the end-all be-all of remembrance; your friends and loved ones keep you in their hearts. It is your choice, it is your life. Also, do not be discouraged if you feel that one or more of your identities is not represented by the archive – get the ball rolling! LHA, for example, is largely populated by white lesbian histories due to its largely white membership, but it is not a white archive. Understandably, the primarily white face of the archive perpetuates self-filtering for those considering joining or donating who are non-white. This is an unfortunate side-effect of the history of the archive–more internal efforts to diversify acquisitions need to take place–but we encourage lesbians of all backgrounds and intersecting identities to donate or volunteer.

Here are some locations you can donate your materials:

- Lesbian Herstory Archives – for lesbian related materials

- Invisible Histories – a memorial archive for deceased LGBTQ+ persons

- Black Unicorn Library and Archive Project – for Black, queer, feminist books

- Queer Digital History Project – a digital archive for queer communities

- LGBT Community Center National History Archive – multimedia queer archive

- Interference Archive – for historic materials relating to social movements

- StoryCorps – for oral histories

When it comes to donating your collections, getting in touch with an archivist is key – they will have a greater knowledge of how to move your digital files and preserve accompanying analog materials. In the case you have older formats such as tapes, vinyl, or floppy disks, they may also have greater access to tools that can digitize them if you both determine that that is in your best interests (as LHA is a volunteer-run archive, we have limited resources than larger institutions). The archivist will also be prepared to ask specific questions about privacy, security, and copyright. If you have managed to save your collection(s) in the most up-to-date technologically and best-to-your-ability organizationally, trust your archivist will be pleased. Leave the technicalities to them. But also, for transparency’s sake, understand that archiving involves bias; every archivist, institution, and accession will impart their own ideas onto a collection, and its future uses and interpretations cannot be fully expected (not to mention the behemoth that is the evolution of technology and the digital sphere). It’s important to find an archive or archivist you trust both to handle your materials and to leave a small part of themselves within the documentation. While this guide is meant to provide tips and tools on how to get started with archiving your works, understand that parts of this may become obsolete, and your and my opinion on archives may change. In any case, my current opinion is that we should take the opportunity to archive our lives because I want to be optimistic and believe in a future where people will continue to care as much as I do. So far now, I will continue to archive.

Thank you for reading this guide on personal digital archiving! I wish you the best of luck in making, preserving, digitizing, and sharing your life and work. If you have any questions, concerns, or suggestions, please reach out to me at esteiner@pratt.edu.

References

- Adair, C. (n.d.). Delete Yr Account: Speculations on Trans Digital Lives and the Anti-Archival, Part I: Are You Sure?. Drecollab.org. Retrieved August 20, 2025, from https://www.drecollab.org/delete-yr-account-part-i/

- Connelly, A. (2025, March 21). Federal Government’s Growing Banned Words List Is Chilling Act of Censorship – PEN America. PEN America. https://pen.org/banned-words-list/

- Gunn, Chelsea. (2018). Putting Personal Digital Archives in Context.

- Human Rights Campaign. (2024, December 4). Attacks on Gender Affirming Care by State Map. Human Rights Campaign. https://www.hrc.org/resources/attacks-on-gender-affirming-care-by-state-map

- Jackson, T. (2018, June 13). It’s Complicated: Restrictions in University Archives. The Academic Archivist. https://academicarchivist.wordpress.com/2018/06/13/its-complicated-restrictions-in-university-archives/

- Newman, J. (2024, January 30). How to digitize and declutter your CDs and DVDs. PCWorld. https://www.pcworld.com/article/2222229/how-to-digitize-and-declutter-your-cds-and-dvds.html

- SexualDiversity.org. (2022, July 17). Queer Theory and Gender Studies. SexualDiversity.org. Retrieved August 20, 2025 from www.sexualdiversity.org/edu/theory/

- Society of American Archivists. (2016, September 12). What Are Archives? | Society of American Archivists. Www2.Archivists.org. https://www2.archivists.org/about-archives

- Yang, A. B. (2018, June 14). How to download your social media data and information. Zapier.com; Zapier. https://zapier.com/blog/download-facebook-twitter-instagram/

Further Reading

- Guide on File Naming and Formats: https://www.dpconline.org/docs/dpc-technology-watch-publications/topical-notes-series/1865-dp-note-4-file-naming-and-formats/file

- Toby Beauchamp. (2019). Going Stealth : Transgender Politics and U.S. Surveillance Practices. Duke University Press.

- [sarah] Cavar. (2025). “Access Fictions: Clarity, Violence, and the Promise of transMad Opacity.” TSQ 1 May 2025; 12 (2): 162–177. doi: https://doi.org/10.1215/23289252-11710358

- Bey, M. (2019). The Blacknesses of Blacknesses: Fugitivity, Feminism, and Transness.

Jace Steiner (they/them) is a white, agender queer currently pursuing a Masters in Library Information Science from Pratt University with a focus on digital archives. They are interested in the intersections of technology, surveillance, queer studies, art, abolition, race, class, and disability. Jace loves webcomics, cosplaying at local raves, and collecting blind-box figurines. They prepared this guide as a final project for their Summer 2025 Special Collections final project.

Really important article. I’m in the process of archiving my papers and materials related to my 50 years of art, teaching and writing practice and this had many useful tips and strategies I will consider.

Thank you for publishing this!

Thank you so much, and we’re glad to hear this will be a resource for you!